What we know

Investment has been a persistent challenge in developing the digital ecosystem

Building the operational foundations of DFS can be prohibitively expensive.

One of the challenges to growth in digital finance has been underinvestment due to a combination of stringent regulatory environments, internal constraints faced by service providers such as the high commercial and operational costs of establishing digital financial services (DFS), and the lack of diverse financing options in emerging markets. Investment plays a key role in extending digital finance to hard-to-reach customers and encourages disruptive, innovative solutions. This Snapshot will focus on how investment can foster the development of digital finance ecosystems, the challenges the industry faces in raising the necessary investment, and the roles of different types of investors.

Underinvestment can risk deepening a digital divide: the cost to extend basic services has been a challenging business case, resulting in providers de-prioritizing hard-to-reach populations. As a result, these populations are at risk of being left behind. As of 2014, mobile money providers in predominantly rural markets were only able to capture 17% of the addressable market compared to 50% of advanced markets.1

A digital finance ecosystem also requires technical rails on which innovations can ride. Recently there has been increasing attention to open and standardized APIs,2 exemplified by Mojaloop—open source software designed for payment interoperability between banks and other financial providers in a country.3 Nevertheless, most individual providers have struggled to justify the much-needed investment in the technical infrastructure required for APIs (such as API documentation and middleware) particularly while bearing the cost of setting up operational foundations (including building an agent network, customer acquisition, and marketing).4

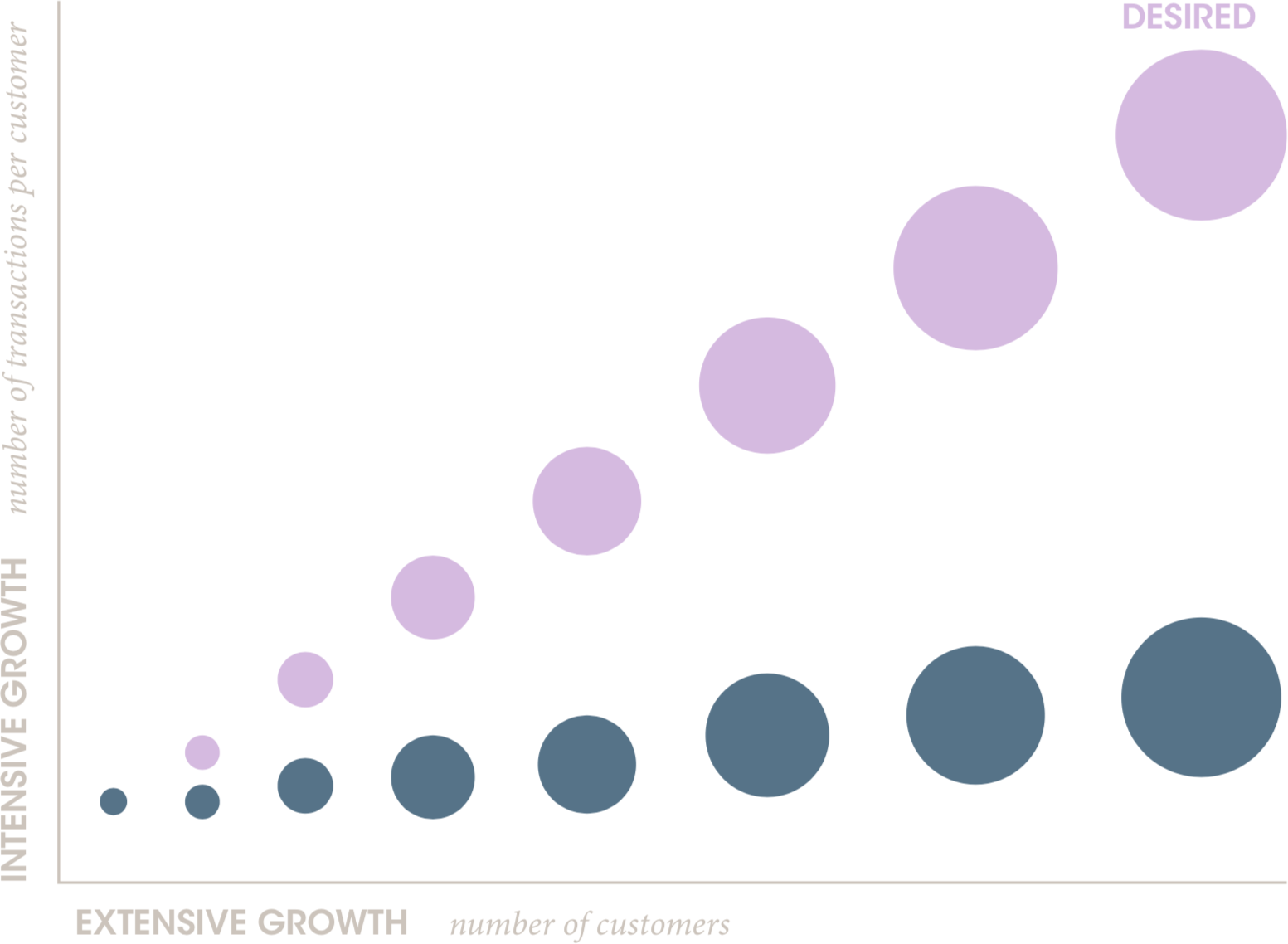

Because investment, whether external or internal, has been a challenge, digital payments players have prioritized services that appeal to the majority of customers (such as person-to-person transfers), rather than “niche solutions” which could increase the number of transactions per customer (i.e., by driving more regular use of digital financial services). As a result, the industry has focused on extensive growth—the number of customers, rather than intensive growth—number of transactions (figure 1). 5 While there are digital players keen to support these niche markets (sophisticated DFS products), such as active aggregators in Uganda6 and pilot projects taking place through FIBR in Tanzania and Ghana,7 a lack of funding and technical infrastructure is holding back growth.

Figure 1: Extensive versus intensive growth of DFS

Source: Morawczynski et al., “Digital Rails: How Providers Can Unlock Innovation in DFS Ecosystems Through Open APIs.”

While the lack of external investment persists, most of the focus around capital markets has been on internal underinvestment. A contributing factor is that the digital finance landscape has centered mostly on mobile money and branchless banking services that are run by large, well-capitalized players—such as mobile network operators (MNOs) and banks. At the same time, due to the high commercial and operational costs of mobile money or branchless banking solutions, providers are reluctant to invest adequately in their early years of operation.8 Therefore, MNOs and banks do not raise funds with VCs exclusively for their digital financial services.

Until now, much of the investment challenge was an internal advocacy challenge to encourage C-level sponsors to allocate investment to a new business line. This is particularly challenging in multi-national businesses whose equity and debt investors have a significantly different risk profile than venture-capital investors. However, as more FinTech entrepreneurs enter payments and digital finance in emerging markets, new investment capital has followed supporting both infrastructure development and accessing hard to reach populations, albeit slowly.

Lack of financing options limits innovation and growth in ecosystem development

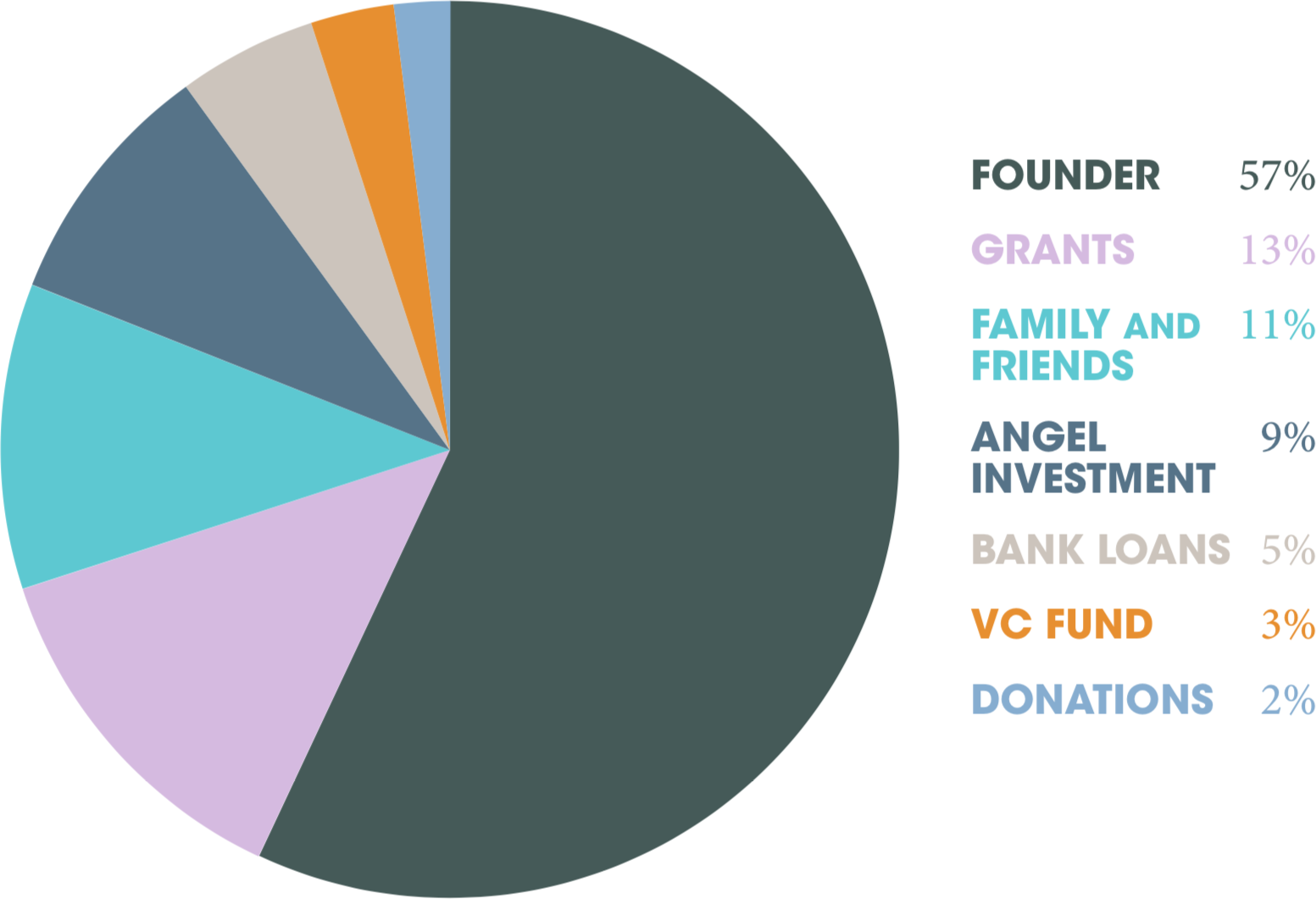

Beyond the incumbent major players of mobile money, other modes of digital finance innovation have struggled to grow in the financial inclusion context and a lack of investment capital has been a key challenge. According to VC4Africa’s 2016 Venture Finance in Africa report, African start-ups (across sectors) disproportionality rely on founder capital (figure 2).9

Figure 2: African start-ups’ source of funding in 2016

Source: VC4Africa

Venture capital and angel investment represent only 12% of the total pool of funding invested across all African tech start-ups in 2016. Within FinTech specifically, the emerging markets pale in comparison to the rest of the world in terms of VC-backed capital. In 2016, although FinTech investments increased by deal value—over $13.8 billion was deployed to a variety of FinTech companies globally, more than double the value of VC investment in FinTech in 201410—investment remained dominated by China, the US, and the UK. With the exception of India (with $272 million across 82 FinTech investments in 2016) and Brazil (with $161 million in value in 2016), the global proportion of VC supporting FinTech development across the rest of Africa, Asia, and Latin America is minimal.11

Improvements needed to unlock investment in digital finance

The aforementioned statistics suggest that FinTechs have struggled to attract funding in Africa and perhaps VCs have made the strategic decision not to invest in the region. There are a myriad of reasons why VCs may be making this decision, including market dynamics that seem to be holding back investors. For investors who have not worked in Africa or other emerging markets, the regulatory environment—including protective intellectual property laws—has acted as a deterrent.12

Similarly, macro dynamics are at play because the lower penetration of smartphones restricts access to consumer data, especially for low-income consumers, and often requires start-ups to be heavily dependent on mobile money providers or banks.13 Moreover, low-income consumers typically do not have a digital store of value besides those offered by mobile money providers (rarely available through APIs). Some of the aforementioned limitations are perhaps contributing to the fact that not that many investors are contributing capital behind FinTech initiatives. 14 The inability of promising FinTechs to attract venture capital funding has limited the innovation potential of the digital finance ecosystem.

While VC capital is synonymous with tech and FinTech investment, it is not the only pool of funding that digital finance players could or should be relying on. Debt, in the form of unsecured bank lending, convertible notes, or microloans, could also help address some of the challenges faced across the tech and digital finance sector. However, debt funding has been no easier to source. The lack of debt capital financing is not unique to tech and FinTech players; it is endemic to the entire MSME sector. Globally, the MSME finance gaps total between $ 2.1 and $ 2.6 trillion according to IFC estimates.15 “Banks are often reluctant to serve MSMEs, given the small loan size and high costs typical of this segment. For other lenders such as microfinance institutions (MFIs), the capacity required to serve MSMEs, particularly assessing business models and risks, remains a major challenge.”16 Moreover, given that funding is disbursed in foreign currency (typically USD), borrowers are exposed to exchange rate changes and must absorb forex risks on their deals. Therefore, local currency denominated debt may be a more attractive option for some digital finance players.

PAYGO energy companies provide a more specific example that impacts the development of a growing energy sector. PAYGO energy companies are restricted in their scale and diversification by lack of access to commercial debt financing—local financial institutions are unwilling to finance the debt due to the insecure nature of the loans in PAYGO portfolios.17 Lendable, a platform that helps alternative lenders access structured financing to scale their operations, offers lenders the chance to set a foreign currency depreciation buffer to absorb forex risks on each deal before that risk affects the repayment of foreign debt financing. Additionally, Lendable offers benefits such as flexible pricing terms for lenders and strong predictive capabilities based on the likelihood of repayment of individual receivables18 that help both potential lenders and investors scale up digital finance operations.

All investment is not good investment: considerations for responsible growth

While a lack of investment obstructed the development of the digital finance ecosystem, it is also important to acknowledge the unintended consequences of philanthropic or private capital. While it is thanks to philanthropic capital that the mobile money industry got underway following the early success of M-PESA and bKash, both of these providers are now widely considered to be market monopolies.19 In the case of Bangladesh, bKash’s position has even been flagged by the Central Bank.20

Philanthropic investments are not the only private investments to meet with unexpected and unintended consequences. Even in developed markets, financial services and venture capital money can be at odds. Venture capitalists look for disruptive or transformational growth opportunities which favor basic tech businesses with low overhead and high-growth opportunities. In a recent article in Entrepreneur magazine, Clint Carter writes that “it’s not that VCs are a bad option. But, many entrepreneurs say, equity investors are better suited for start-ups with whiz-bang proprietary technology and a realistic strategy to scale and sell quickly.”21

However, financial services are rarely “whiz-bang;” they are, and should be, risk-based services. “Banks are necessarily incrementalist institutions. And ‘disruption’ in incremental institutions is nothing more than a representation of risk.”22 As VCs and young start-ups chase significant growth, it is critical that investment harnesses responsible growth. For example, the pursuit of growth in P2P lending in China resulted in fraudulent and reckless implementations in 2015. Many businesses became no more than Ponzi schemes, one of the worst of which resulted in losses of $7.6 billion.23 In part this was due to a lack of adequate regulatory oversight, but it also demonstrates how quickly an exciting market can implode through its own irresponsibility.

Looking ahead to a changing landscape, it is important to unlock much needed investment to support the development of the digital finance ecosystem. However, as the digital finance ecosystem develops it must incorporate responsible financing principles. Part of the approach to responsible financing must be to address the issue of customers’ risks to strengthen the foundation of digital finance. When mass market customers trust services, they respond by using them on a regular basis.

Notable new learning

Market dynamics have had a positive influence on the landscape

Rise of smartphones will see new entrants, greater competition, and more innovation

One of the most obvious changes to directly impact the ecosystem is the wider availability of affordable smartphones. Smartphone penetration in Africa doubled between 2014 to 2016, reaching 226 million connections.24 As a mechanism to drive usage, “smartphones present a great opportunity because of the user interface and user experience and it’s easy to inform and educate people about how to use products. Plus, there is this big data element.”25

Firstly, smartphones bring new innovation where channel access has been restricted by USSD access or usability. Until now, limited smartphone penetration has meant reliance on the USSD channel, which is restrictive and limited in terms of user experience.26 While the OTT (over-the-top) threat has been on the radar for a while,27 activity from payment start-ups as well as big messaging players, such as WhatsApp, has increased recently.28

However, even traditional MNOs have had the opportunity to experiment with better design because of the increases penetration of smartphones. While they initially tended to dump a USSD-style menu into a smartphone, providers—with the support of partners and designers—are changing the way they engage with customers. Wave Money in Myanmar, with the help of CGAP, has not only implemented but published their insights on designing for smartphones.29 This kind of smartphone innovation will feed greater innovation that, hopefully, will feed greater investment in digital finance.

Finally, smartphones allow for the exploration of new business models, particularly the use of big data to improve the delivery of small credit (e.g., by using non-traditional data to establish customers’ credit worthiness). It is widely expected that most non-traditional data will be derived from smartphone activity.30 This is already being done, albeit at a relatively small scale. As previously mentioned, Lendable is helping alternative lenders—who utilize non-traditional data to develop client credit scores—access structured financing to scale their operations.31

Donor investments have borne fruit resulting in new appetite from private and philanthropic financiers

Donor funding played a crucial “experimental capital” role that laid the foundation for new innovation and opportunity in developing digital finance ecosystems. This funding, which initially helped prove the DFS business model, has encouraged investment appetite from private and philanthropic financiers. For instance, although most African start-ups bootstrap their early days, there is increasing support for entrepreneurs in the form of tech hubs. In 2016, tech hubs in Africa had “more than doubled in less than a year.”32

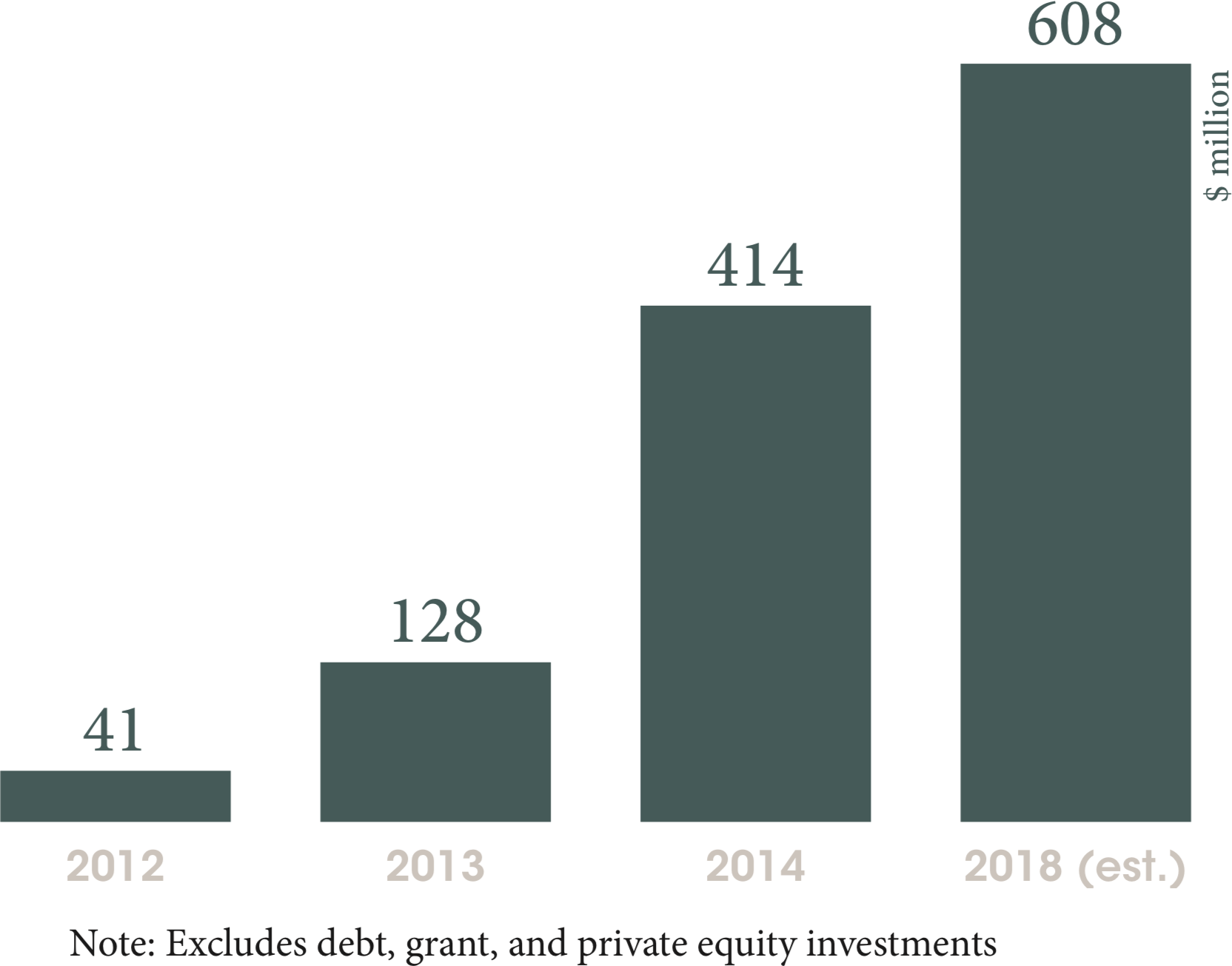

While hubs alone do not directly result in an increase in investment capital, research shows that these hubs “act as a nexus between local technology communities and investors, academia, technology companies and the wider private sector.”33 In addition to the rising number of hubs, there is increasing demand from the investment community. In their 2015 Mobile Economy report for sub-Saharan Africa, the GSMA estimated that VC investment in African tech start-ups would increase by nearly 50% in 2018 (figure 3).34 This predicted rise in investment has been linked to the bourgeoning sub-Saharan Africa tech ecosystem, including the growth of tech incubators and the rise of junior and senior “techies,” as well as existing investment from grant donations, global tech companies, and VC funding within the tech space.35

Figure 3: Venture capital funding in African tech start-ups

Source: GSMA, “The Mobile Economy: Sub-Saharan Africa 2015,” 2015

Early-stage digital finance innovation in particular is already showing signs of the predicted growth. Over the past few years a new mix of social impact capital has emerged, supporting early stage innovators with grant, equity, or debt funding. Among these players are Accion Frontier Inclusion Fund, The Catalyst Fund, The DFS Lab, The Global Innovation Fund and the Mastercard Foundation Fund for Rural Prosperity. In addition, there is a new quantum of financial commitment thanks to the Universal Financial Access 2020 goal, led by the World Bank. “The World Bank has set a target to help enable 400 million adults to be reached through knowledge, technical and financial support, while IFC has set a target to help enable 600 million adults to be reached through investment and advisory services.”36

While still in early stages, these new entrants could catalyze new investor appetite to support digital finance innovation.

Implications

Funding strategies shift toward market development

As the digital finance industry develops, the role capital plays will continue to evolve. As demonstration cases bear fruit and the opportunity of digital finance becomes more tangible, investment—in all forms—will need to take a more systemic approach. “Rather than strengthening individual market actors (e.g. financial service providers [FSPs]), a systemic approach to financial inclusion requires funders to set the right conditions for these actors to adopt new, more inclusive behaviors beyond initial partners and the duration of the funder’s intervention.”37

A market systems approach does not preclude investment in an individual FSP. Instead, a market systems approach contextualizes an individual investment in the broader dynamic of the digital finance ecosystem. According to CGAP’s research, funders of financial inclusion who apply a market systems approach invest in market development using the following considerations: facilitating interventions that change the incentives of the market system, taking the whole market (rather than just the supply side) into account, and focusing on crowding-in market actors through transparent and well-structured incentives to ensure a flexible approach that can respond to changes in the market dynamic.

Other funds have also referenced this market systems approach as an important part of their investment mandate. A recent blog from the Global Innovation Fund cited the importance of investing in systemic change, particularly to achieve their goal of supporting the UN Sustainable Development Goals.38 FIBR’s ecosystem approach in Ghana has also used aspects of the market systems approach. To advance financial inclusion, they have identified six crucial success factors all of which are deeply tied to the market system as a whole. These include: growth of mobile money, open APIs, access to affordable credit, access to risk capital and venture financing, data protection, and sharing and business partnership environment.39

Closing the investment gap with more than just capital

As noted above, the investment gap is beginning to narrow as more investors express interest and enthusiasm in the FinTech opportunities in emerging markets. Accelerators—fixed-term, cohort-based, mentor-driven programs to support early stage start-ups—have gained traction in recent years. Significantly, accelerators do not simply provide financial capital, they help to establish the operational foundation and sustainable growth of businesses. Because the start-up ecosystem in emerging markets is still nascent, accelerators in emerging marks are likewise nascent, relative to those in more advanced markets. However, there is an opportunity to apply lessons from successful accelerators in order to increase the likelihood of support for FinTech innovators in these emerging markets.

According to research released by the Brookings Institute,40 start-ups that joined a leading accelerator were more likely to raise funding and exit sooner than similar start-ups that did not participate in an accelerator. However, not all accelerators are created equal; the research revealed several key indicators of successful accelerators. These included establishing effective mentoring and creating a useful and consistent way to engage with mentors throughout the program, designing an absorbable and relevant curriculum that founders can implement in their businesses immediately, and building a culture and network around the community that “feeds on itself and perpetuates a lifetime process of learning.”41

Conclusion

There is increasing data to suggest that emerging market start-ups are as credentialed and committed as their developed market counterparts, however, they function in ecosystems that are less networked, less funded, and generally less supported.42 It would be prudent for the digital finance community to address the barriers that stand in the way of innovation and development. As highlighted in this Snapshot these barriers are: the required technical infrastructure to proliferate innovation; the lack of diverse investors in the digital finance landscape; philanthropic investment that goes beyond capital; and an in-depth understanding on the part of investors of the macro-dynamics (including regulation) at play in each of their local markets.

10 Must Reads in this space

- The 2016 VC Fintech Investment Landscape. February 2017.

- Kazeem, Yomi. African Start-Ups Are Securing More Investment—but There’s Still Room for Growth. Quartz, May 2016.

- Burjorjee, Deena M., and Barbara Scola. A Market Systems Approach to Financial Inclusion: Guideline for Funders. CGAP, September 1, 2015.

- Moretto, Louise, and Barbara Scola. Development Finance Institutions and Financial Inclusion: From Institution-Building to Market Development. CGAP, March 2017.

- Roberts, Peter W, Genevieve Edens, Abigayle Davidson, Edward Thomas, Cindy Chao, Kerri Heidkamp, and Jo-Hannah Yeo. Accelerating Start-Ups in Emerging Markets: Insights from 43 Programs. The Global Accelerator Learning Initiative, May 2017.

- Accion Venture Lab. Bridging the Small Business Credit Gap through Innovative Lending. Accion, November 2016.

- Almazán, Mireya, and Nicolas Vonthron. Mobile Money Profitability: A Digital Ecosystem to Drive Healthy Margins. GSMA, November 14.

- FIBR. Alternative Lending: Landscaping the Funding Models for Lending Fintech Companies, n.d.

- FIBR The Environment for ‘FIBR FinTech’ in Ghana. FIBR, July 2016.

- Morawczynski, Olga, Michel Hanouch, Lesley-Ann Vaughan, and Xavier Faz. Digital Rails: How Providers Can Unlock Innovation in DFS Ecosystems Through Open APIs. CGAP, November 2016.

Bibliography

- Accion Venture Lab. “Bridging the Small Business Credit Gap through Innovative Lending.” Accion, November 2016. https://www.accion.org/sites/default/files/Bridging%20the%20Small%20Business%20Credit%20Gap%20Through%20Innovative%20Lending%20by%20Accion%20Venture%20Lab.pdf?_ga=1.159619710.2135856374.1480944912.

- Almazán, Mireya, and Elisa Sitbon. “SMARTPHONES & MOBILE MONEY—The Next Generation of Digital Financial Inclusion.” GSMA, July 2014. http://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/2014_MMU_Smartphones-and-Mobile-Money-The-Next-Generation-of-Digital-Financial-Inclusion_Web.pdf.

- Almazán, Mireya, and Nicolas Vonthron. “Mobile Money Profitability: A Digital Ecosystem to Drive Healthy Margins.” GSMA, November 2014. http://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/2014_Mobile-money-profitability-A-digital-ecosystem-to-drive-healthy-margins.pdf.

- Beeson, Will. The Omidyar Network on Fintech, Financial Inclusion and Social Impact. Rebank: Banking for the Future. Accessed May 21, 2017. https://bankingthefuture.com/omidyar-network-fintech-financial-inclusion-social-impact/.

- Bright, Jake, and Aubrey Hruby. “The Rise Of Silicon Savannah And Africa’s Tech Movement,” n.d. https://techcrunch.com/2015/07/23/the-rise-of-silicon-savannah-and-africas-tech-movement/.

- Burjorjee, Deena M., and Barbara Scola. “A Market Systems Approach to Financial Inclusion: Guidelines for Funders.” CGAP, September 1, 2015. http://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/Consensus-Guidelines-A-Market-Systems-Approach-to%20Financial-Inclusion-Sept-2015_0.pdf.

- Camner, Gunnar. “Launching GSMA Mobile Money APIs to Raise Industry Capabilities.” GSMA (blog), n.d. https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/programme/mobile-money/launching-gsma-mobile-money-apis-to-raise-industry-capabilities.

- Carter, Clint. “For Entrepreneurs, Venture Capital Is Not Always the Best Option.” Entrepreneur (blog), June 2017. https://www-entrepreneur-com.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/www.entrepreneur.com/amphtml/294554.

- CGAP. “Partner with CGAP to Open APIs,” May 2017. http://www.cgap.org/news/partner-cgap-open-apis.

- Costa, Arjuna, Anamitra Deb, and Michael Kubzansky. “Big Data, Small Credit: Digital Revolution and Its Impact on Emerging Market Consumers.” Omidyar Network, 2015. https://www.omidyar.com/sites/default/files/file_archive/insights/Big%20Data,%20Small%20Credit%20Report%202015/BDSC_Digital%20Final_RV.pdf.

- Dahir, Abdi Latif. “The Number of Tech Hubs across Africa Has More than Doubled in Less than a Year.” Quarz (blog), August 17, 2016. https://qz.com/759666/the-number-of-tech-hubs-across-africa-has-more-than-doubled-in-less-than-a-year/.

- Darkwa, David, and Rashmi Pillai. “Lessons from Aggregator-Enabled Digital Payments in Uganda.” CGAP (blog), February 2016. http://www.cgap.org/blog/lessons-aggregator-enabled-digital-payments-uganda.

- DeRose, Chris. “The Trouble with Fintech (or Why ‘Now’ Is the Time for DLT).” Coin Desk (blog), May 3, 2017. http://www.coindesk.com/the-trouble-with-fintech-and-why-now-is-the-time-for-dlt/.

- Faz, Xavier, and Daniel Waldron. “Digitally Financed Energy: How Off-Grid Solar Providers Leverage Digital Payments and Drive Financial Inclusion.” CGAP, May 2016. http://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/Brief-Digitally-Financed-Energy-Mar-2016.pdf.

- FIBR. “Alternative Lending: Landscaping the Funding Models for Lending Fintech Companies,” n.d.

- ———. “Lendable: Case Study of a Marketplace Lending Platform in East Africa,” 2017. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5682a94969a91ad70f60a07c/t/5968c0cdf7e0abc8788d42c8/1500037330470/FIBR+Briefing+note+4+Lendable+FINAL+July+2017.pdf.

- ———. “Paygo Solar: Lighting the Way for Flexible Financing and Services,” 2017. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5682a94969a91ad70f60a07c/t/5968d184e45a7c330fcea1ec/1500041609397/FINAL+FIBR+Briefing+note+PAYGo+Solar+July+2017.pdf%0A.

- ———. “The Environment for ‘FIBR FinTech’ in Ghana.” FIBR, July 2016. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5682a94969a91ad70f60a07c/t/57a19de3d482e9ab0a374180/1470209512919/FIBR+briefing+note+%231-+Environment+for+FIBR+FinTech+in+Ghana+V4.1+Medium.pdf.

- ———. “The Lean Product Waltz: Data-Driven User Research & Research-Driven Data Analysis,” n.d. NA.

- Gilman, Lara, and Gunnar Camner. “Beyond the Technical Solution: Considerations for Sharing APIs with 3rd Parties.” GSMA (blog), May 29, 2014. http://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/programme/mobile-money/beyond-the-technical-solution-considerations-for-sharing-apis-with-3rd-parties.

- Gilman, Lara, Janet Shulist, Maxime de Lisle, and Emmanuel de Dinechin. “Spotlight on Rural Supply: Critical Factors to Create Successful Mobile Money Agents,” October 2015. http://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/2015_GSMA_Spotlight-on-Rural-Supply-Critical-factors-to-create-successful-mobile-money-agents.pdf.

- GSMA. “The Mobile Economy 2016.” GSMA, March 21, 2016. https://www.gsmaintelligence.com/research/?file=97928efe09cdba2864cdcf1ad1a2f58c&download.

- ———. “The Mobile Economy: Sub-Saharan Africa 2015,” 2015. https://www.gsmaintelligence.com/research/?file=721eb3d4b80a36451202d0473b3c4a63&download.

- Hanouch, Michel, and Gregory Chen. “Promoting Competition in Mobile Payments: The Role of USSD.” CGAP, February 13, 2015. http://www.cgap.org/publications/promoting-competition-mobile-payments-role-ussd.

- Hathaway, Ian. “Accelerating Growth: Startup Accelerator Programs in the United States.” Brookings, February 2016. https://www.brookings.edu/research/accelerating-growth-startup-accelerator-programs-in-the-united-states/.

- Johnstone, Zach. “Financing the Sustainable Development Goals.” Global Innovation Fund (blog), May 12, 2017. https://globalinnovation.fund/financing-the-sustainable-development-goals/.

- Jones, Brad. “Wave Money Myanmar: The Power of Smartphone Design.” CGAP (blog), October 2016. http://www.cgap.org/blog/wave-money-myanmar-power-smartphone-design.

- Kazeem, Yomi. “African Start-Ups Are Securing More Investment—but There’s Still Room for Growth.” Quartz (blog), May 2016. https://qz.com/691106/african-start-ups-are-securing-more-investment-but-theres-still-room-for-growth/.

- McKay, Claudia, and Rafe Mazer. “10 Myths About M-PESA: 2014 Update.” CGAP (blog), October 2014. http://www.cgap.org/blog/10-myths-about-m-pesa-2014-update.

- Miller, Matthew, and Shu Zhang. “China’s $7.6 Billion Ponzi Scam Highlights Growing Online Risks.” Reuters, February 2016. http://uk.reuters.com/article/us-china-fraud/chinas-7-6-billion-ponzi-scam-highlights-growing-online-risks-idUKKCN0VB2O1.

- “Monopoly Situation Prevails in MFS Market: BB Official.” NewAge, February 2017. http://www.newagebd.net/print/article/8757.

- Morawczynski, Olga, Michel Hanouch, Lesley-Ann Vaughan, and Xavier Faz. “Digital Rails: How Providers Can Unlock Innovation in DFS Ecosystems Through Open APIs.” CGAP, November 2016. https://www.cgap.org/blog/riding-%E2%80%9Crails%E2%80%9D-unlocking-innovation-open-apis.

- Nyambura-Mwaura, Helen. “Inventors Struggle to Protect Patents in Africa.” Reuters, July 2014. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-africa-investment/inventors-struggle-to-protect-patents-in-africa-idUSKBN0FM0HQ20140717.

- Roberts, Peter W, Genevieve Edens, Abigayle Davidson, Edward Thomas, Cindy Chao, Kerri Heidkamp, and Jo-Hannah Yeo. “Accelerating Start-Ups in Emerging Markets: Insights from 43 Programs.” The Global Accelerator Learning Initiative, May 2017.

- Schwaab, Dr. Jan, and Sabine Olthof. “Technology Hubs: Creating Space for Change: Africa’s Technology Innovation Hubs,” 2013. http://10innovations.alumniportal.com/fileadmin/10innovations/dokumente/GIZ_10innovations_Technology-Hubs_Brochure.pdf.

- Sur, David del. “How Does the Inclusive Fintech Landscape Compare to Mainstream Fintech?” FIBR (blog), June 2016. https://blog.fibrproject.org/how-does-the-inclusive-fintech-landscape-compare-to-mainstream-fintech-d08ce4e5c721.

- “The 2016 VC Fintech Investment Landscape.” February 2017. https://www.slideshare.net/innovatefinance/the-2016-vc-fintech-investment-landscape-71849828/1.

- “UFA 2020 Overview: Universal Financial Access by 2020.” The World Bank (blog), April 20, 2017. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/brief/achieving-universal-financial-access-by-2020?CID=FAM_TT_FinanceMarkets_EN_EXT.

- “WhatsApp All Set to Launch P2P Payment Services in India?” Economic Times India, April 7, 2017. http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/money/whatsapp-all-set-to-launch-p2p-payment-services-in-india/articleshow/58002902.cms.

Notes

& acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

Lara Gilman wrote this Snapshot, with further inputs from David Edelstein and Maha Khan. This Snapshot was supported by the Mastercard Foundation.

Notes

The views presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and the Partnership, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Mastercard Foundation or Caribou Digital.

For questions or comments please contact us at ideas@financedigitalafrica.org.

Recommended citation

Partnership for Finance in a Digital Africa, “Snapshot 11: What ecosystem improvements will unlock investment in digital finance?” Farnham, Surrey, United Kingdom: Caribou Digital Publishing, 2017. https://www.financedigitalafrica.org/snapshots/11/2017/.

About the Partnership

The Mastercard Foundation Partnership for Finance in a Digital Africa (the “Partnership”), an initiative of the Foundation’s Financial Inclusion Program, catalyzes knowledge and insights to promote meaningful financial inclusion in an increasingly digital world. Led and hosted by Caribou Digital, the Partnership works closely with leading organizations and companies across the digital finance space. By aggregating and synthesizing knowledge, conducting research to address key gaps, and identifying implications for the diverse actors working in the space, the Partnership strives to inform decisions with facts, and to accelerate meaningful financial inclusion for people across sub-Saharan Africa.

This is work is licensed under the Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/.

Readers are encouraged to reproduce material from the Partnership for Finance in a Digital Africa for their own publications, as long as they are not being sold commercially. We request due acknowledgment, and, if possible, a copy of the publication. For online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the www.financedigitalafrica.org website.

-

Gilman et al., “Spotlight on Rural Supply: Critical Factors to Create Successful Mobile Money Agents.” ↩

-

CGAP, “Partner with CGAP to Open APIs”; Camner, “Launching GSMA Mobile Money APIs to Raise Industry Capabilities.” ↩

-

Mojaloop is funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and was released in October 2017. Mojaloop was designed by a team of tech and FinTech companies: Ripple, Dwolla, ModusBox, Software Group, and Crosslake Technologies. ↩

-

Gilman and Camner, “Beyond the Technical Solution: Considerations for Sharing APIs with 3rd Parties.” ↩

-

Morawczynski et al., “Digital Rails: How Providers Can Unlock Innovation in DFS Ecosystems Through Open APIs.” ↩

-

Darkwa and Pillai, “Lessons from Aggregator-Enabled Digital Payments in Uganda.” ↩

-

FIBR, “Lendable: Case Study of a Marketplace Lending Platform in East Africa”; FIBR, “Paygo Solar: Lighting the Way for Flexible Financing and Services”; FIBR, “The Lean Product Waltz: Data-Driven User Research & Research-Driven Data Analysis.” ↩

-

Almazán and Vonthron, “Mobile Money Profitability: A Digital Ecosystem to Drive Healthy Margins.” ↩

-

Kazeem, “African Start-Ups Are Securing More Investment—but There’s Still Room for Growth.” ↩

-

del Sur, “How Does the Inclusive Fintech Landscape Compare to Mainstream Fintech?” ↩

-

“The 2016 VC Fintech Investment Landscape.” ↩

-

Nyambura-Mwaura, “Inventors Struggle to Protect Patents in Africa.” ↩

-

del Sur, “How Does the Inclusive Fintech Landscape Compare to Mainstream Fintech?” ↩

-

del Sur. ↩

-

Accion Venture Lab, “Bridging the Small Business Credit Gap through Innovative Lending.” ↩

-

Accion Venture Lab. ↩

-

Faz and Waldron, “Digitally Financed Energy: How Off-Grid Solar Providers Leverage Digital Payments and Drive Financial Inclusion.” ↩

-

FIBR, “Alternative Lending: Landscaping the Funding Models for Lending Fintech Companies”; FIBR, “Lendable: Case Study of a Marketplace Lending Platform in East Africa.” ↩

-

McKay and Mazer, “10 Myths About M-PESA: 2014 Update.” ↩

-

“Monopoly Situation Prevails in MFS Market: BB Official.” ↩

-

Carter, “For Entrepreneurs, Venture Capital Is Not Always the Best Option.” ↩

-

DeRose, “The Trouble with Fintech (or Why ‘Now’ Is the Time for DLT).” ↩

-

Miller and Zhang, “China’s $7.6 Billion Ponzi Scam Highlights Growing Online Risks.” ↩

-

GSMA, “The Mobile Economy 2016.” ↩

-

Beeson, The Omidyar Network on Fintech, Financial Inclusion and Social Impact. ↩

-

Hanouch and Chen, “Promoting Competition in Mobile Payments: The Role of USSD.” ↩

-

Almazán and Sitbon, “SMARTPHONES & MOBILE MONEY—The Next Generation of Digital Financial Inclusion.” ↩

-

“Whatsapp All Set to Launch P2P Payment Services in India?” ↩

-

Jones, “Wave Money Myanmar: The Power of Smartphone Design.” ↩

-

Costa, Deb, and Kubzansky, “Big Data, Small Credit: Digital Revolution and Its Impact on Emerging Market Consumers.” ↩

-

FIBR, “Lendable: Case Study of a Marketplace Lending Platform in East Africa”; FIBR, “Alternative Lending: Landscaping the Funding Models for Lending Fintech Companies.” ↩

-

Dahir, “The Number of Tech Hubs across Africa Has More than Doubled in Less than a Year.” ↩

-

Schwaab and Olthof, “Technology Hubs: Creating Space for Change: Africa’s Technology Innovation Hubs.” ↩

-

GSMA, “The Mobile Economy: Sub-Saharan Africa 2015.” ↩

-

Bright and Hruby, “The Rise Of Silicon Savannah And Africa’s Tech Movement.” ↩

-

“UFA 2020 Overview: Universal Financial Access by 2020.” ↩

-

Burjorjee and Scola, “A Market Systems Approach to Financial Inclusion: Guidelines for Funders.” ↩

-

Johnstone, “Financing the Sustainable Development Goals.” ↩

-

FIBR, “The Environment for ‘FIBR FinTech’ in Ghana.” ↩

-

Hathaway, “Accelerating Growth: Startup Accelerator Programs in the United States.” ↩

-

Hathaway. ↩

-

Roberts et al., “Accelerating Start-Ups in Emerging Markets: Insights from 43 Programs.” ↩