What we know

For reasons ranging from lack of digital skills to cultural constraints, it is common practice for some individuals to rely on others in order to utilize certain technologies and technology-enabled services. As both Burrell and Rangaswamy show,1 shared, community, and intermediated use of technology are common and essential aspects of rural life and informal economies.

Defining shared use in digital finance

Shared use in digital finance can either refer to the sharing of a digital finance account—with one SIM card, and therefore one account, shared between multiple users—or the sharing of a mobile device, meaning users may have their own SIM cards, and therefore digital finance account, but rely on a shared mobile phone to access their digital finance network. For example, in Rwanda more adults (25%) are reported as having access to a mobile money account, than being mobile money account users (23%).2

While there is adequate data around shared use of mobile phones, unfortunately information and analysis is limited with regard to the shared use of digital financial services. Finclusion data from 2015 reports that nine in ten Ghanaians (91%) own a mobile phone, compared to 74% of Kenyans, 72% of Tanzanians, 58% of Ugandans, and 47% of Rwandans.3 In Rwanda, while 47% of all adults own a phone, 67% report having access to a mobile phone, with just under half of Rwandans reporting that they borrow a phone “less frequently than once a week, or never.”4 While this analysis focuses on phone access and ownership, it has obvious implications for shared use in digital finance.

Defining intermediated use in technology and digital finance

The subject of intermediation has been, primarily, the interest of two groups: firstly, human-computer interaction (HCI) researchers and designers who have sought to understand interactions between users and technology, and secondly, digital finance researchers and practitioners.

From the HCI field, Sambasivan et al. explain: “intermediation by another person occurs when the primary user is not capable of using a device entirely on their own.”5 Parikh and Ghosh first identified the importance of recognizing and designing for the “secondary user” in intermediated digital finance services.6 They outlined a continuum of intermediated use, which ranged from clients with access to a mobile device to completely “indirect” transactions wherein an agent conducts a transaction on behalf of a client.7 Ghosh expanded the definition of intermediated use further to look beyond time-bound specific interactions between a client and an agent at the point of transaction.8 For example, his definition of intermediated use integrates practices in which an agent holds and transfers a client’s money at a later time when the system is down.

From the perspective of digital finance providers and researchers, intermediated use of digital financial services (DFS) involves a client that requires help from a third party, usually an agent, in order to complete a transaction over a digital finance platform. This includes activities such as over-the-counter (OTC) transactions and direct deposits. The ITU DFS Focus group defines intermediated use as “a transaction that the agent conducts on behalf of a sender/recipient or both from either the sender’s or agent’s mobile money account.”9

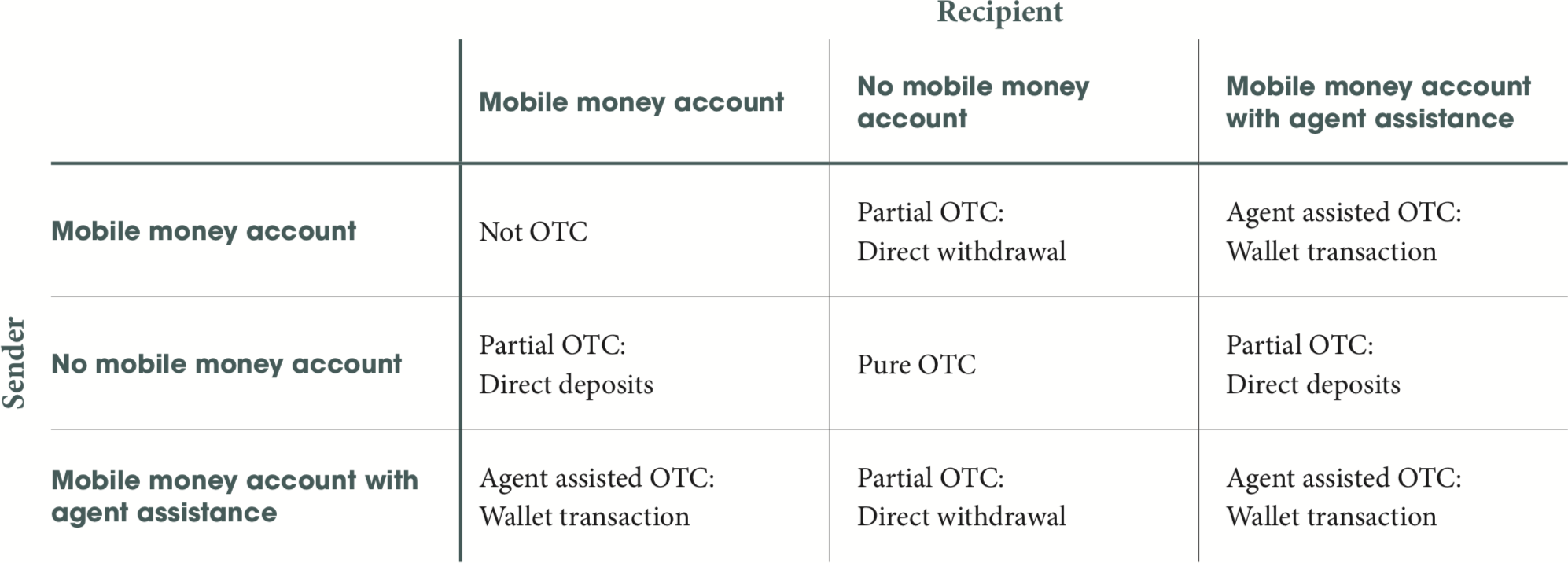

A pure OTC transaction, as indicated below in Figure 1 from the ITU DFS Focus group’s report,10 takes place when both the sender and receiver utilize an agent to conduct a digital financial transaction without the use of a mobile money (or digital finance) account.

Figure 1: Defining OTC using the parties involved

Source: ITU-T, Focus Group Digital Financial Services, 2016

OTC is particularly popular in South Asian markets such as Pakistan and Bangladesh. In Bangladesh, InterMedia reports that only 33% of mobile money users had a registered account in 2016, with the majority continuing to conduct OTC transactions.11 In Pakistan this is even lower, with 7% of users registered with an account in 2016, and 93% conducting OTC transactions.12

In this Snapshot we focus on intermediated use of digital financial services, primarily looking at the impact of over-the-counter (OTC) and direct deposits on the evolution and adoption of digital financial services. As highlighted in the conclusion, more research is needed to tackle the question of shared use both in terms of the sharing of digital finance accounts and the sharing of mobile devices to access these accounts. While the question of intermediated use seems most important now, interesting insights into shared use may emerge as smartphone penetration grows and we find cases in which people access more than one “virtual” wallet through a single SIM or device. We hope to tackle the question of “shared use” in the next update of the Snapshot.

Motivations for, and benefits of, intermediation in digital finance

From the client perspective

Practitioners and HCI researchers have examined the motivation for intermediated transactions to better understand how to increase adoption. The HCI body of work has focused primarily on client motivations. Sambasivan et al.13 summarize these as: a fear of the technology due to unfamiliarity with the technology or a lack of self-efficacy; a lack of textual literacy, numeracy, or digital operational skills; existing habits of dependency that are transferred to technology use; and the cost of owning a device and access constraints related to age, gender, or cultural barriers. In each of these cases, the option of turning to a more digitally enabled individual allows the client to participate in digital finance. Previous work by Ramírez et al.,14 examining the role of infomediation and infomediaries, shows that infomediaries (“information intermediaries” 15 such as agents) can “contribute to developing the capacity and confidence among users to use and explore ICTS with increased independence.” Sambasivan et al.16 find a similar pattern when they note that agents can inform clients about digital finance services and instruct clients in how to use them, leading to an uptake of services.

Similarly, digital finance practitioners have outlined many motivations for OTC and direct deposit transactions among clients. Research has found that a lack of experience with technology and formal financial institutions or issues with literacy and numeracy can lead to customers that do “not access their accounts at all or they ask friends, family, or agents to conduct transactions on their behalf and often for a fee.”17 OTC is also a convenient mode of transaction for clients that struggle to meet know-your-customer (KYC) registration requirements.18

The ability of clients to pass on the responsibility of a transaction has been noted as both a motivator for clients’ preference of OTC and a contributing factor in lowering the barrier of entry to digital finance. By giving the agent full responsibility for a transaction, and any potential adverse outcome, an unsure client may gain the necessary confidence to use a digital financial service. Bakhshi notes that with OTC “the customer does not need to change his behaviour or learn a new, possibly intimidating, technology.”19

Despite these motivations, research by InterMedia in Bangladesh found that OTC use is generally driven by its ability to fulfill clients’ needs, rather than by a lack of awareness of mobile money accounts or issues surrounding registration and use of self-guided transactions.20 They argue that “in a market-led environment, service delivery should be determined by user demand. OTC, ironically, thus is client-centric, as users prefer it to accounts to fulfil their needs.” 21 It is therefore important to note that OTC and direct deposit are also used by individuals who are not intimidated by technology but are rather seeking to avoid the hassle of wallet transactions.

From a wider ecosystem perspective

Beyond clients, digital finance practitioners have looked at motivations for intermediated use from the perspective of a range of actors in the digital finance ecosystem, from providers to agents.

The digital finance ecosystem’s continued support for transactions mediated by agents is largely due, arguably, to the relative success it has had in driving use of digital finance in a selection of less developed markets. Data from Pakistan and Bangladesh demonstrates the reach of digital finance through OTC. Easypaisa, a mobile money service delivered through Telenor Pakistan and Tameer Microfinance Bank, reports nearly 16.2 million OTC customers.22 InterMedia reports that 39% of Bangladeshis have accessed mobile money through bKash. While the number of OTC customers globally is decreasing, OTC transactions are on the rise, up from 37.4 million transactions in June 2015 to 44.3 million transactions in June 2016.23 In fact, 94% of Zoona’s (a third party provider in Zambia) revenues, which exceeded $8 million in 2014, come from fees charged to P2P over-the-counter transactions.24 Beyond these success stories, OTC dominates other markets at varying stages of digital finance development from Senegal25 to Cote D’Ivoire.26 OTC is also seen as a stepping stone by which customers come to sign up for a registered account and access the more advanced products and services that come with it. Research shows that 58% of bKash mobile money registered users tested the services via OTC use before registering.27

MicroSave’s research also highlights that OTC can benefit product evolution and development.28 While customers are conducting OTC transactions, providers can collect data on their preferences and usage. Providers can then build future products around this data and develop compelling cases for mobile money account use.

With regards to agents’ motivations, the potentially high revenues that agents can earn from supporting OTC transactions is notable.29 In OTC dominant markets “agents are king,” and thus have the power to choose which service provider they use based on commissions and other incentives. As a result, in markets such as Pakistan, a “commission war” has ensued between providers competing to offer higher commissions to agents in order to win their share of the OTC market.30 The Helix research therefore finds that agents have healthy revenues in Pakistan31 and increasing profitability in Bangladesh.32

Risks of intermediated transactions

Despite these benefits, intermediation—particularly OTC intermediation—also poses risks to all the actors involved. On the client side, clients can be at risk of being defrauded by agents. In some cases, agents may charge clients extra fees to provide a service,33 or an agent may recommend a particular MNO’s mobile money product because of its superior commissions rather than its superior product specifications. Further, sharing a PIN number with an agent or another intermediary has obvious risk implications.

Another client-level concern that both Sambasivan34 and Wright35 warn of is the potential lack of learning and agency that occurs when a client sheds all the responsibilities of transacting to the agent. This could mean that the client fails to learn about new products and services and never moves beyond remittance and payment products. Wright argues that this could entirely defeat the goal of a fully inclusive digital economy as envisioned by Radcliffe and Voorhies36 in their four stages of the pathway to financial inclusion.

On the provider side, OTC can increase the risk of money laundering and terrorism financing, especially with informal OTC transactions wherein the user is not identified.37 However, in markets such as Pakistan where transactions are biometrically registered, it is hard to bypass the system and conduct an informal OTC transaction. The risk of money laundering or terrorism financing is therefore higher in markets where informal, unenforced OTC or direct deposits are facilitated.

MicroSave points to the impact a lack of revenue generated through P2P transactions can have on providers’ profitability.38 GSMA has also highlighted that OTC transactions can negatively affect revenue streams due to the high level of operating expenses spent on agent commissions.39 As mentioned above, in OTC markets rather than the customer being king, agents hold power over providers. In the pure OTC model (see the table on Page 1), in which customers have no SIM card and thus no affiliation to a brand or service, the agent decides which service to use simply based on the best commissions available. OTC methodology therefore “switches the location of the battlegrounds for market share from the customer (as seen in mobile wallet-based markets) to the agent.”40 Rather than focusing on customers and product development, providers in OTC markets are constantly having to increase their commissions relative to competitors in order to incentivize agents to use their services. In Pakistan, however, providers have decided as a group to stop the commissions war because of the negative impact it was having on their revenues. Instead they focus on wallet transition. As a result of shifting the focus away from agents, “providers facing a higher demand for their services win.”41

Other potential risks for providers include the fear that if a person begins with OTC they will have a more difficult transition to account use at a later stage42 or that OTC may limit product evolution. With high OTC usage, products are limited to “one-time transactional financial services.”43 In the pure OTC model wherein customers transact without a mobile money account, the opportunity to introduce “sophisticated” digital financial services, such as savings, credit, and insurance, is highly limited. Some providers have expanded their product range beyond the traditional OTC offerings of domestic remittances and bill payments. Easypaisa has launched “Easypay,” an online, e-commerce payment solution in which users can book a product online and pay for it in an Easypaisa shop without requiring an Easypaisa mobile money account. In Senegal, Wari and Joni Joni have expanded to offer a pioneering cross-border remittance product, accessible through both mobile wallets and OTC.44 However, these products still fall into the bucket of “one-time transactions financial services.” While agents could be used to promote a diversity of financial services and create a level of awareness that would not otherwise exist, users would still need their own accounts to access more sophisticated digital finance offerings such as savings, credit, and insurance. The argument that OTC may limit product evolution has, however, been counter-argued by MicroSave’s research, and is worth noting.45

Notable new learning

A better understanding of the risks and rewards of OTC

A number of publications have been released around OTC transactions and the benefits and challenges they bring to digital finance providers, agents, and their end clients. MicroSave provides a good analysis of the OTC industry by discussing and analyzing five issues surrounding OTC including AML (anti-money laundering) and CFT (combatting the financing of terrorism) risks, providers’ profitability, limitations of product development, and volatility in market share.46 The paper concludes by outlining the pros and cons of OTC for each stakeholder involved and recommendations for how the industry can address these issues.

Implications

Transitioning from OTC to wallets must be the long-term goal

As demonstrated, OTC can catalyze uptake of digital finance, and it may be an efficient means of quickly driving awareness, adoption, and use. However, the risks of long-term OTC use must be understood. Specific risks include how the ultimate reliance on agent networks can harm providers’ profitability, and how a failure to transition customers to wallets will negatively impact long-term product evolution and ecosystem development. As a result, providers must focus on developing strategies to transition customers from OTC to wallets. While more developed markets such as Pakistan47 and Bangladesh already have strategies underway, nascent markets such as Senegal, Zambia, and Cote D’Ivoire need to ensure they have the appropriate planning in place to manage this transition.

The digital finance community needs to understand shared, secondary-user scenarios

While a lot of time and money has been invested in researching intermediated use in terms of OTC transactions and direct deposit, fewer studies have looked at shared use of digital finance accounts. The digital finance industry would benefit from a deeper understanding of shared use and its roles and implications for future adoption and product development. This is especially important for hard to reach, excluded populations such as women.

Conclusion

Not everyone uses digital finance as it was originally intended. From individuals repurposing digital financial services to meet their own needs to clients using intermediaries to conduct their transactions, nuanced uses of digital finance make our analysis both interesting and complex. In this Snapshot we have discussed both the benefits and risks associated with the intermediated use of digital financial services and the role it plays within the digital finance ecosystem. While many markets have benefited from such assisted transactions, we believe that transitioning from OTC to wallets must be the long-term goal. While we are interested in better understanding shared use in digital finance, there is a dearth of information and analysis on this thematic area. We hope that we will be able to tackle this question in more detail with the next update of the Snapshot.

10 Must Reads in this space

- McCaffrey, Mike, Graham A. N. Wright, and Anup Singh. OTC: A Digital Stepping Stone, or a Dead End Path? The Helix Institute of Digital Finance, August 11, 2016.

- Ghosh, Ishita. Contextualizing Intermediated Use in the Developing World: Findings from India & Ghana. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 355–359. CHI ’16. New York, NY, USA: ACM, 2016. doi:10.1145/2858036.2858594.

- Bakhshi, Pawan. Beware The OTC Trap: Are Stakeholders Satisfied?, May 2014.

- Parikh, J. S., and Kaushik Ghosh. Understanding and Designing for Intermediated Information Tasks in India. IEEE Pervasive Computing 5, no. 2 (April 2006): 32–39. doi:10.1109/MPRV.2006.41.

- Bakhshi, Pawan. Beware The OTC Trap, May 2014.

- Ramírez, Ricardo, Balaji Parthasarathy, and Andrew Gordon. From Infomediaries to Infomediation at Public Access Venues: Lessons from a 3-Country Study. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development: Full Papers—Volume 1, 124–132. ICTD ’13. New York, NY, USA: ACM, 2013.

- Singh, Anup, and Graham Wright. Over the Counter Transactions: A Threat to or a Facilitator for Digital Finance Ecosystems?>, November 2016.

- Ogwal, Isaac Holly. The OTC Trap—Impact on the Business Case for Uganda’s Mobile Network Operators. Accessed January 17, 2017.

- Sambasivan, Nithya, Ed Cutrell, Kentaro Toyama, and Bonnie Nardi. Intermediated Technology Use in Developing Communities. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2583–2592. CHI ’10. New York, NY, USA: ACM, 2010.

- Wesolowski, Amy, Nathan Eagle, Abdisalan M. Noor, Robert W. Snow, and Caroline O. Buckee. Heterogeneous Mobile Phone Ownership and Usage Patterns in Kenya. Edited by Sergio Gómez. PLoS ONE 7, no. 4 (April 25, 2012): e35319.

Bibliography

- Almazán, Mireya, and Nicolas Vonthron. “Mobile Money Profitability: A Digital Ecosystem to Drive Healthy Margins.” GSMA, November 14. http://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/2014_Mobile-money-profitability-A-digital-ecosystem-to-drive-healthy-margins.pdf.

- Bakhshi, Pawan. “Beware The OTC Trap,” May 2014. http://blog.microsave.net/beware-the-otc-trap/.

- Butt, Sidra, Imran Khan, and Vera Bersudskaya. “State of Play: Insights on the Evolution of Pakistan’s Mobile Money Agent Network.” Karandaaz (blog), October 2017. https://karandaaz.com.pk/blog/state-play-insights-evolution-pakistans-mobile-money-agent-network/.

- Byun, Jungwon. “Zoona: A Case Study on Third Party Innovation in Digital Finance.” FSD Zambia, August 2015. http://www.fsdzambia.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Zoona-A-Case-Study-on-Third-Party-Innovation-in-Digital-Finance.pdf.

- Engels, Judyth, and Joanne Oparo. “Customer Profiles to Improve Reach of MTN Mobile Savings and Loan Product in Rural Uganda,” July 2016. http://uncdf.org/en/customer-profiles-improve-reach-mtn-mobile-savings-and-loan-product-rural-uganda.

- Financial Inclusion Insights (FII). “Rwanda National Survey Report.” InterMedia, February 2015. http://finclusion.org/uploads/file/reports/FII%20Rwanda%202014%20National%20Survey%20Report.pdf.

- Ghosh, Ishita. “Contextualizing Intermediated Use in the Developing World: Findings from India & Ghana.” In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 355–359. CHI ’16. New York, NY, USA: ACM, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1145/2858036.2858594.

- GSMA. “State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money: Decade Edition: 2006-2016,” February 2017. http://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/GSMA_State-of-the-Industry-Report-on-Mobile-Money_Final-27-Feb.pdf.

- Financial Inclusion Insights (FII). “Bangladesh Wave 4 Report FII Tracker Survey,” September 2017. http://finclusion.org/uploads/file/Bangladesh%20Wave%204%20Report_20_Sept%202017.pdf.

- ———. “Pakistan Wave 4 Report FII Tracker Survey,” June 2017. http://finclusion.org/uploads/file/Pakistan%20Wave%204%20Report%2019-July-2017(1).pdf.

- Khan, Maha, and Omar Moen Malik. “From OTC to Mobile Accounts: Easypaisa’s Journey,” January 2017. http://www.helix-institute.com/blog/otc-mobile-accounts-easypaisa%E2%80%99s-journey.

- Khan, Maha, and Mike McCaffrey. “The Powerful Agents & Fractured Markets of Pakistan,” June 2015. http://www.helix-institute.com/blog/powerful-agents-fractured-markets-pakistan-0.

- Khan, Maha, and Anup Singh. “Debunking the Myth of OTC.” The Helix Institute of Digital Finance (blog), June 2016. http://www.helix-institute.com/blog/debunking-myth-otc.

- Koning, Antonique, and Monique Cohen. “Enabling Customer Empowerment: Choice, Use, and Voice,” March 2015. https://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/Brief-Enabling-Customer-Empowerment-Mar-2015_0.pdf.

- Lonie, Susan, Martinez Meritxell, Christopher Tullis, and Rita Oulai. “The Mobile Banking Customer That Isn’t: Drivers of Digital Financial Services Inactivity in CÔTE D’IVOIRE.” The Mastercard Foundation, IFC, 2015. http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/fe1c69804aa2b52e9f60df9c54e94b00/Final+CDI+Inactivity+Report+ENGLISH.pdf?MOD=AJPERES.

- Mas, Ignacio. “My PIN Is 4321,” September 2012. http://www.cgap.org/blog/my-pin-4321.

- McCaffrey, Mike, Graham A. N. Wright, and Anup Singh. “OTC: A Digital Stepping Stone, or a Dead End Path?” The Helix Institute of Digital Finance, August 11, 2016. http://www.helix-institute.com/sites/default/files/Publications/OTC_Digital_Stepping_Stone_or_Dead_End_Path.pdf.

- Mehrotra, Aakash, and Maha Khan. “Agent Network Accelerator Survey: Pakistan Country Report 2014.” The Helix Institute of Digital Finance, May 2015. http://www.helix-institute.com/sites/default/files/Publications/Agent%20Network%20Accelerator%20Pakistan%20Country%20Report%202014.pdf.

- Mirzoyants, Anastasia. “Mobile Money in Uganda The Financial Inclusion Tracker Surveys Project—Use, Barriers and Opportunities.” InterMedia, October 2012. https://www.microfinancegateway.org/sites/default/files/mfg-en-paper-mobile-money-in-uganda-use-barriers-and-opportunities-oct-2012.pdf.

- MM4P. “Consumer Behaviours in Senegal: Analysis and Findings,” September 2016. http://uncdf.org/sites/default/files//Documents/senegal_rh_-_consumer_behaviours_en.pdf.

- Ogwal, Isaac Holly. “The OTC Trap—Impact on the Business Case for Uganda’s Mobile Network Operators.” Accessed January 17, 2017. http://blog.microsave.net/the-otc-trap-impact-on-the-business-case-for-ugandas-mobile-network-operators/.

- Orakzai, Mejzgaan. “Mobile Money: The OTC and Agent Dilemma.” Karandaaz (blog), March 2016. https://karandaaz.com.pk/blog/mobile-money-the-otc-and-agent-dilemma/.

- Parikh, J. S., and Kaushik Ghosh. “Understanding and Designing for Intermediated Information Tasks in India.” IEEE Pervasive Computing 5, no. 2 (April 2006): 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1109/MPRV.2006.41.

- Radcliffe, Daniel, and Rodger Voorhies. “A Digital Pathway to Financial Inclusion.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, December 11, 2012. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2186926.

- Ramírez, Ricardo, Balaji Parthasarathy, and Andrew Gordon. “From Infomediaries to Infomediation at Public Access Venues: Lessons from a 3-Country Study.” In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development: Full Papers—Volume 1, 124–132. ICTD ’13. New York, NY, USA: ACM, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1145/2516604.2516621.

- Rangaswamy, Nimmi, and Sumitra Nair. “The Mobile Phone Store Ecology in a Mumbai Slum Community: Hybrid Networks for Enterprise.” Information Technologies & International Development 6, no. 3 (September 9, 2010): 51–65.

- Sambasivan, Nithya, Ed Cutrell, Kentaro Toyama, and Bonnie Nardi. “Intermediated Technology Use in Developing Communities.” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2583–2592. CHI ’10. New York, NY, USA: ACM, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1145/1753326.1753718.

- Singh, Anup, and Graham Wright. “Over the Counter Transactions: A Threat to or a Facilitator for Digital Finance Ecosystems?,” November 2016. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-T/focusgroups/dfs/Documents/12_2016/ITUFGDFS_REPORT%20ON%20OTC%20_11-2016.pdf.

- The Helix Institute of Digital Finance. “Agent Network Accelerator Survey: Senegal Country Report 2015,” May 2016. http://www.helix-institute.com/sites/default/files/Publications/Senegal%20Country%20Report%20-%20En%20FINAL%20VERSION%20HELIX.pdf.

- Tiwari, Akhand, and Pragya Jain. “Agent Network Accelerator Survey: Bangladesh Report 2016.” The Helix Institute of Digital Finance, August 2016. http://www.helix-institute.com/sites/default/files/Publications/160809%20Bangladesh%20Country%20Report.pdf.

- Wright, Graham. “Over The Counter Transactions—Liberation Or A Trap?—Part I,” December 2014. http://blog.microsave.net/over-the-counter-transactions-liberation-or-a-trap-part-i/.

- ———. “Over The Counter Transactions—Liberation Or A Trap? Part II,” December 2014. http://blog.microsave.net/over-the-counter-transactions-liberation-or-a-trap-part-ii/.

Notes

& acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

Annabel Schiff and David Hutchful wrote this Snapshot. This Snapshot was supported by the Mastercard Foundation.

Notes

The views presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and the Partnership, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Mastercard Foundation or Caribou Digital.

For questions or comments please contact us at ideas@financedigitalafrica.org.

Recommended citation

Partnership for Finance in a Digital Africa, “Snapshot 7: What are the roles of intermediated and shared use?” Farnham, Surrey, United Kingdom: Caribou Digital Publishing, 2017. https://www.financedigitalafrica.org/snapshots/7/2017/.

About the Partnership

The Mastercard Foundation Partnership for Finance in a Digital Africa (the “Partnership”), an initiative of the Foundation’s Financial Inclusion Program, catalyzes knowledge and insights to promote meaningful financial inclusion in an increasingly digital world. Led and hosted by Caribou Digital, the Partnership works closely with leading organizations and companies across the digital finance space. By aggregating and synthesizing knowledge, conducting research to address key gaps, and identifying implications for the diverse actors working in the space, the Partnership strives to inform decisions with facts, and to accelerate meaningful financial inclusion for people across sub-Saharan Africa.

This is work is licensed under the Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/.

Readers are encouraged to reproduce material from the Partnership for Finance in a Digital Africa for their own publications, as long as they are not being sold commercially. We request due acknowledgment, and, if possible, a copy of the publication. For online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the www.financedigitalafrica.org website.

-

Rangaswamy and Nair, “The Mobile Phone Store Ecology in a Mumbai Slum Community.” ↩

-

Financial Inclusion Insights (FII), “Rwanda National Survey Report,” 33. ↩

-

Financial Inclusion Insights (FII), “Rwanda National Survey Report,” 7. ↩

-

Financial Inclusion Insights (FII), 25. ↩

-

Sambasivan et al., “Intermediated Technology Use in Developing Communities.” ↩

-

Parikh and Ghosh, “Understanding and Designing for Intermediated Information Tasks in India.” ↩

-

Parikh and Ghosh. ↩

-

Ghosh, “Contextualizing Intermediated Use in the Developing World.” ↩

-

Singh and Wright, “Over the Counter Transactions: A Threat to or a Facilitator for Digital Financial Ecosystem.” ↩

-

Singh and Wright. ↩

-

Financial Inclusion Insights (FII), “Bangladesh Wave 4 Report FII Tracker Survey.” ↩

-

Financial Inclusion Insights (FII), “Pakistan Wave 4 Report FII Tracker Survey,” 38. ↩

-

Sambasivan et al., “Intermediated Technology Use in Developing Communities.” ↩

-

Ramírez, Parthasarathy, and Gordon, “From Infomediaries to Infomediation at Public Access Venues.” ↩

-

Ramírez, Parthasarathy, and Gordon. ↩

-

Sambasivan et al., “Intermediated Technology Use in Developing Communities.” ↩

-

Koning and Cohen, “Enabling Customer Empowerment: Choice, Use, and Voice.” ↩

-

Wright, “Over The Counter Transactions – Liberation Or A Trap?,” December 2014. ↩

-

Bakhshi, “Beware The OTC Trap.” ↩

-

Financial Inclusion Insights (FII), “Bangladesh Wave 4 Report FII Tracker Survey,” 37. ↩

-

McCaffrey, Wright, and Singh, “OTC: A Digital Stepping Stone, or a Dead End Path?” ↩

-

Khan and Malik, “From OTC to Mobile Accounts: Easypaisa’s Journey.” ↩

-

GSMA, “State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money: Decade Edition: 2006-2016.” ↩

-

Byun, “Zoona: A Case Study on Third Party Innovation in Digital Finance.” ↩

-

MM4P, “Consumer Behaviours in Senegal: Analysis and Findings”; Engels and Oparo, “Customer Profiles to Improve Reach of MTN Mobile Savings and Loan Product in Rural Uganda”; The Helix Institute of Digital Finance, “Agent Network Accelerator Survey: Senegal Country Report 2015.” ↩

-

Ghosh, “Contextualizing Intermediated Use in the Developing World.” ↩

-

Financial Inclusion Insights (FII), “Bangladesh Wave 4 Report FII Tracker Survey,” 36. ↩

-

McCaffrey, Wright, and Singh, “OTC: A Digital Stepping Stone, or a Dead End Path?” ↩

-

Mehrotra and Khan, “Agent Network Accelerator Survey: Pakistan Country Report 2014,” 23. ↩

-

Orakzai, “Mobile Money: The OTC and Agent Dilemma.” ↩

-

Mehrotra and Khan, “Agent Network Accelerator Survey: Pakistan Country Report 2014.” ↩

-

Tiwari and Jain, “Agent Network Accelerator Survey: Bangladesh Report 2016.” ↩

-

Mirzoyants, “Mobile Money in Uganda The Financial Inclusion Tracker Surveys Project – Use, Barriers and Opportunities.” ↩

-

Sambasivan et al., “Intermediated Technology Use in Developing Communities.” ↩

-

Wright, “Over The Counter Transactions – Liberation Or A Trap?,” December 2014. ↩

-

Radcliffe and Voorhies, “A Digital Pathway to Financial Inclusion.” ↩

-

McCaffrey, Wright, and Singh, “OTC: A Digital Stepping Stone, or a Dead End Path?” ↩

-

Ogwal, “The OTC Trap – Impact on the Business Case for Uganda’s Mobile Network Operators.” ↩

-

Almazán and Vonthron, “Mobile Money Profitability: A Digital Ecosystem to Drive Healthy Margins.” ↩

-

Khan and McCaffrey, “The Powerful Agents & Fractured Markets of Pakistan.” ↩

-

Butt, Khan, and Bersudskaya, “State of Play: Insights on the Evolution of Pakistan’s Mobile Money Agent Network.” ↩

-

Bakhshi, “Beware The OTC Trap.” ↩

-

Mehrotra and Khan, “Agent Network Accelerator Survey: Pakistan Country Report 2014.” ↩

-

Khan and Singh, “Debunking the Myth of OTC.” ↩

-

McCaffrey, Wright, and Singh, “OTC: A Digital Stepping Stone, or a Dead End Path?” ↩

-

McCaffrey, Wright, and Singh. ↩

-

Khan and McCaffrey, “The Powerful Agents & Fractured Markets of Pakistan.” ↩